The Bering Sea is an ocean. Bering Sea: geographical location, description

It is located in its northern part. It is separated from the boundless ocean waters by the Aleutian and Commander Islands. In the north, through the Bering Strait, it connects with the Chukchi Sea, which is part of the Arctic Ocean. The reservoir washes the shores of Alaska, Chukotka, Kamchatka. Its area is 2.3 million square meters. km. Average depth is 1600 meters, the maximum is 4150 meters. The volume of water is 3.8 million cubic meters. km. The length of the reservoir from north to south is 1.6 thousand km, and from west to east it is 2.4 thousand km.

Historical reference

Many experts believe that during the last ice age the sea level was low, and therefore the Bering Strait was land. This so-called Bering bridge, through which the inhabitants of Asia fell into the territory of the North and South America in deep antiquity.

This reservoir was explored by the Dane Vitus Bering, who served in the Russian fleet as a captain-commander. He studied the northern waters in 1725-1730 and 1733-1741. During this time, he carried out two Kamchatka expeditions and discovered part of the islands of the Aleutian ridge.

In the 18th century, the reservoir was called the Kamchatka Sea. It was first named the Bering Sea at the initiative of the French navigator Charles Pierre de Fleurieu at the beginning of the 19th century. This name was fully fixed by the end of the second decade of the 19th century.

general description

Sea bottom

In its northern part, the reservoir is shallow, thanks to the shelf, the length of which reaches 700 km. The southwestern part is deep water. Here the depth reaches up to 4 km in some places. The transition from shallow water to the deep ocean floor is carried out along a steep underwater slope.

Water temperature and salinity

IN summer time the surface layer of water warms up to 10 degrees Celsius. In winter, the temperature drops to -1.7 degrees Celsius. The salinity of the upper sea layer is 30-32 ppm. The middle layer at a depth of 50 to 200 meters is cold and practically does not change throughout the year. The temperature here is -1.7 degrees Celsius, and the salinity reaches 34 ppm. Below 200 meters, the water warms up, and its temperature rises to 4 degrees Celsius with a salinity of 34.5 ppm.

The Bering Sea receives such rivers as the Yukon in Alaska with a length of 3100 km and the Anadyr with a length of 1152 km. The latter carries its waters through the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug of Russia.

Bering Sea on the map

Islands

The islands are concentrated on the boundaries of the reservoir. The main ones are considered Aleutian Islands representing an archipelago. It stretches from the coast of Alaska towards Kamchatka and has 110 islands. Those, in turn, are divided into 5 groups. There are 25 volcanoes on the archipelago, and the largest is the Shishaldin volcano with a height of 2857 meters above sea level.

Commander Islands includes 4 islands. They are located in the southwestern part of the considered reservoir. Pribylov Islands located north of the Aleutian Islands. There are four of them: St. Paul, St. George, Otter and Walrus Island.

Diomede Islands(Russia) consist of 2 islands (Ratmanov Island and Kruzenshtern Island) and several small rocks. They are located in the Bering Strait at approximately the same distance from Chukotka and Alaska. The Bering Sea is also St. Lawrence Island in the southernmost part Bering Strait. It is part of the state of Alaska, although it is located closer to Chukotka. Experts believe that in ancient times it was part of the isthmus connecting 2 continents.

Nunivak Island located off the coast of Alaska. Among all the islands belonging to the reservoir in question, it is the second largest after St. Lawrence. In the southern part of the Bering Strait is also located island of St. Matthew, owned by the USA. Karaginsky island located near the coast of Kamchatka. The highest point on it (High Mountain) is 920 meters above sea level.

sea coast

The sea coast is characterized by capes and bays. From bays to Russian coast can be called Anadyr, washing the shores of Chukotka. Its continuation is the Gulf of the Cross, located to the north. Karaginsky Bay is located off the coast of Kamchatka, and Olyutorsky Bay is located to the north. Deep in the coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Gulf of Korfa is wedged.

Bristol Bay is located off the southwestern coast of Alaska. To the north are smaller bays. This is Kuskokwim, into which the river of the same name flows, and Norton Bay.

Climate

In summer, the air temperature rises to 10 degrees Celsius. In winter it drops to -20-23 degrees Celsius. The Bering Sea is covered with ice by the beginning of October. The ice melts by July. That is, the reservoir is covered with ice for almost 10 months. In some places, such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, ice can be present all year round.

Marine mammals such as bowhead and blue whales, sei whales, fin whales, humpback whales, and sperm whales live in the sea. There are also northern fur seals, beluga, seals, walruses, polar bears. Up to 40 species of different birds nest on the coast. Some of them are unique. In total, about 20 million birds breed in this region. 419 species of fish are registered in the reservoir. Salmon, pollock, king crab, Pacific cod, halibut, and Pacific perch are of commercial value.

The further development of the ecosystem of the reservoir under consideration is uncertain. The region has recorded a modest but steady growth over the past 30 years. sea ice. This was in sharp contrast to the seas of the Arctic Ocean, where the ice surface is steadily decreasing.

The most northern of the Far Eastern seas of Russia is the Bering Sea. Its water area is located between America and Asia. The sea is separated from the Pacific Ocean by the Commander and Aleutian Islands. A map of the Bering Sea shows that its boundaries are mostly natural. Only in some areas it has conditional boundaries. The Bering Sea is considered one of the deepest and big seas planets. It covers an area of about 2315 thousand square meters. km. Its average depth is 1640 m. The deepest point is 4151 m. The reservoir got its name thanks to the researcher Bering, who studied it in the 18th century. Until that time, on the maps of Russia, the sea was called Bobrov or Kamchatka.

Geographical characteristic

The sea has a mixed continental-oceanic type and is considered marginal. There are few islands in its vast territory. The large islands are the Aleutian, Commander, Karaginsky, Nelson, St. Matthew, St. Paul and others. The sea is distinguished by a complex indented coastline. It has many bays, bays, capes, peninsulas, straits. The Pacific Ocean has a great influence on the Bering Sea. Water exchange with it occurs through the straits: Bering, Kamchatka, etc. The Bering Strait connects the water area with the Northern Arctic Ocean and the Chukchi Sea. In the central and southwestern regions there are deep-sea places that are surrounded by coastal shallows. The relief of the seabed is even, practically without depressions.

Climate in the Bering Sea area

Almost the entire water area is dominated by the subarctic climate. In the Arctic region, only the northern part of the sea is located, and in the zone of temperate latitudes, the southern margin. Therefore, weather conditions vary in different parts of the Bering Sea. Continental climate features are manifested in areas located from 55 degrees latitude. The eastern region of the sea is warmer than the western one.

The role of the Bering Sea in the life of the country

This sea is intensively exploited by people. Today, such important sectors of the economy as maritime transport and fishing are developed there. A huge number of valuable salmon fish are caught in the Bering Sea. Fishing is also carried out for such fish as flounder, pollock, cod and herring. Fishing for sea animals and whales is practiced. Freight transportation is developed in the Bering Sea, the Far East Sea Basin and the Northern Sea Route are joined there. The coast of the Bering Sea continues to be actively studied. Scientists are investigating issues related to further development seafaring and fishing.

The Bering Sea is located in the North Pacific Ocean. It is separated from it by the Commander and Aleutian Islands, borders on the Chukchi Sea through the Bering Strait. Through the Chukchi Sea, from the Bering Sea you can go to the Arctic Ocean. In addition, this sea washes the coast of two countries: Russian Federation and the United States of America.

Physical and geographical position of the Bering Sea

The coastline of the sea is heavily indented with capes and bays. The largest bays, which are located on the coast of Russia, are the bays of Anadyr, Karaginsky, Olyutorsky, Korfa, Cross. And on the coast of North America - the bays of Norton, Bristol, Kuskokwim.

Only two flow into the sea major rivers: Anadyr and Yukon.

The Bering Sea also has many islands. Basically they are located on the border of the sea. The Russian Federation includes the Diomede Islands (the western one is Ratmanov Island). Commander Islands, Karaginsky Island. To the territory of the United States of America - the Pribylov Islands, the Aleutian Islands, the Diomede Islands (the eastern one is Krusenstern Island), St. Lawrence Island, Nunivak, King Island, St. Matthew Island.

In summer, the air temperature over the waters of the sea ranges from plus 7 to plus 10 degrees Celsius. In winter, it drops to minus 23 degrees. The salinity of the water varies on average from 33 to 34.7 percent.

Seabed relief

The relief of the seabed in the northeastern part is marked by the continental shelf. Its length is more than 700 kilometers. the sea is rather shallow.

The southwestern section is deep water and has depths of up to 4 kilometers. These two zones can be divided conditionally along the isobath of 200 meters.

The transition point of the continental shelf to the ocean floor is marked by a significantly steep continental slope. The maximum depth of the Bering Sea is in the southern part - 4151 meters. The bottom on the territory of the shelf is covered with a mixture of sand, shell rock and gravel. In deep water areas, the bottom is covered with diatomaceous silt.

temperature and salinity

The layer near the sea surface, about 50 meters deep, warms up to 10 degrees Celsius throughout the entire area of \u200b\u200bthe water area in the summer months. In winter, the average minimum temperature is about minus 3 degrees. Salinity up to 50 meters in depth reaches 32 ppm.

The layer near the sea surface, about 50 meters deep, warms up to 10 degrees Celsius throughout the entire area of \u200b\u200bthe water area in the summer months. In winter, the average minimum temperature is about minus 3 degrees. Salinity up to 50 meters in depth reaches 32 ppm.

Below 50 and up to 200 meters there is an intermediate water layer. The water here is colder, practically does not change the temperature all year round (-1.7 degrees Celsius). Salinity reaches 34 percent.

Deeper than 200 meters the water becomes warmer. Its temperature ranges from 2.5 to 4 degrees, and the salinity level is approximately 34 percent.

Ichthyofauna of the Bering Sea

There are approximately 402 different species of fish in the Bering Sea. Among these 402 species, you can find 9 species of sea goby, 7 species of salmon fish and many others. About 50 species of fish are commercially caught. Crabs, shrimps and cephalopods are also caught in the waters of the sea.

Among the mammals living in the Bering Sea there are ringed seals, seals, bearded seals, lionfish and walruses. The list of cetaceans is also extensive. Among them you can meet a gray whale, narwhal, bowhead whale, Japanese (or southern) whale, fin whale, humpback whale, sei whale, blue northern whale. On the Chukchi Peninsula, there are many walrus and seal rookeries.

Bering Sea

The largest of the Far Eastern seas washing the shores of Russia, the Bering Sea is located between two continents - Asia and North America - and is separated from the Pacific Ocean by the islands of the Commander-Aleutian arc. Its northern border coincides with the southern border of the Bering Strait and stretches along the line of Cape Novosilsky (Chukotsky Peninsula) - Cape York (Seward Peninsula), the eastern border runs along the coast of the American continent, the southern one - from Cape Khabuch (Peninsula Alaska) through the Aleutian Islands to Cape Kamchatsky, western - along the coast of the Asian continent.

The Bering Sea is one of the largest and deep seas peace. Its area is 2315 thousand km 2, volume - 3796 thousand km 3, average depth - 1640 m, maximum depth - 4097 m. The area with depths of less than 500 m occupies about half of the entire area of the Bering Sea, which belongs to the marginal seas of the mixed - ocean type.

There are few islands in the vast expanses of the Bering Sea. Apart from the border Aleutian island arc and the Commander Islands, there are large Karaginsky Islands in the west and several islands (St. Lawrence, St. Matthew, Nelson, Nunivak, St. Paul, St. George, Pribylova) in the east.

The coastline of the Bering Sea is heavily indented. It forms many bays, bays, peninsulas, capes and straits. For the formation of many natural processes in this sea, straits are especially important, providing water exchange with Pacific Ocean. The total area of their cross section is approximately 730 km 2, the depths in some of them reach 1000-2000 m, and in Kamchatsky - 4000-4500 m, as a result of which water exchange occurs not only in the surface, but also in the deep horizons. The cross-sectional area of the Bering Strait is 3.4 km 2, and the depth is only 60 m. The waters of the Chukchi Sea practically do not affect the Bering Sea, but the Bering Sea waters play a very significant role in the Chukchi Sea.

The borders of the seas of the Pacific Ocean

Different parts of the coast of the Bering Sea belong to different geomorphological types of coasts. The shores are mostly abrasion, but there are also accumulative ones. The sea is surrounded mainly by high and steep shores, only in the middle part of the western and eastern coasts wide strips of flat lowland tundra approach it. Narrower strips of the lowland coast are located near the mouths of small rivers in the form of a deltaic alluvial valley or border the tops of bays and bays.

Landscapes of the coast of the Bering Sea

Bottom relief

The main morphological zones are clearly distinguished in the relief of the bottom of the Bering Sea: the shelf and insular shoals, the continental slope and the deep-water basin. The shelf zone with depths up to 200 m is mainly located in the northern and eastern parts of the sea and occupies more than 40% of its area. Here it adjoins the geologically ancient regions of Chukotka and Alaska. The bottom in this area is a vast, very gently sloping underwater plain 600-1000 km wide, within which there are several islands, hollows and small bottom elevations. The continental shelf off the coast of Kamchatka and the islands of the Commander-Aleutian ridge looks different. Here it is narrow, and its relief is very complex. It borders the shores of geologically young and very mobile land areas, within which intense and frequent manifestations of volcanism and seismic activity are common.

The continental slope stretches from the northwest to the southeast approximately along the line from Cape Navarin to about. Unimac. Together with the island slope zone, it occupies approximately 13% of the sea area, has depths from 200 to 300 m, and is characterized by a complex bottom topography. The zone of the continental slope is dissected by submarine valleys, many of which are typical submarine canyons, deeply cut into the seabed and having steep and even steep slopes. Some canyons, especially near the Pribylov Islands, are distinguished by their complex structure.

The deep-water zone (3000-4000 m) is located in the southwestern and central parts of the sea and is bordered by a relatively narrow strip of coastal shallows. Its area exceeds 40% of the sea area. The bottom relief is very calm. It is characterized by the almost complete absence of isolated depressions. The slopes of some bottom depressions are very gentle; these depressions are weakly isolated. Of the positive forms, the Shirshov Ridge stands out, but it has a relatively shallow depth on the ridge (mainly 500–600 m with a saddle of 2500 m) and does not come close to the base of the island arc, but ends in front of the narrow but deep (about 3500 m) Ratmanov Trench. The greatest depths of the Bering Sea (more than 4000 m) are located in the Kamchatka Strait and near the Aleutian Islands, but they occupy a small area. Thus, the bottom relief determines the possibility of water exchange between separate parts of the sea: without restrictions within the depths of 2000–2500 m and with some limitation (determined by the section of the Ratmanov trough) to depths of 3500 m.

Bottom relief and currents of the Bering Sea

Climate

The geographical position and large spaces determine the main features of the climate of the Bering Sea. It is located almost entirely in the subarctic climate zone, only the most Northern part(north of 64° N) belongs to the Arctic zone, and the southernmost part (south of 55° N) belongs to the zone of temperate latitudes. In accordance with this, climatic differences between different areas of the sea are also determined. North of 55-56°N in the climate of the sea (especially its coastal areas) features of continentality are noticeably pronounced, but in areas remote from the coast they are much weaker. South of these parallels, the climate is mild, typically maritime. It is characterized by small daily and annual air temperature amplitudes, high cloud cover and a significant amount of precipitation. As you get closer to the coast, the influence of the ocean on the climate decreases. Due to stronger cooling and less significant heating of the part of the Asian continent adjacent to the sea, the western regions of the sea are colder than the eastern ones. Throughout the year, the Bering Sea is under the influence of constant centers of atmospheric action - the Polar and Hawaiian maxima, the position and intensity of which change from season to season, and the degree of their influence on the sea changes accordingly. It is no less influenced by seasonal large-scale baric formations: the Aleutian Low, the Siberian High, and the Asian Depression. Their complex interaction determines the seasonal features of atmospheric processes.

In the cold season, especially in winter, the sea is mainly influenced by the Aleutian Low, the Polar High, and the Yakutsk spur of the Siberian Anticyclone. Sometimes the impact of the Hawaiian high is felt, which at this time occupies the extreme southern position. Such a synoptic situation leads to a wide variety of winds, the entire meteorological situation over the sea. At this time, winds of almost all directions are observed here. However, the northwestern, northern and northeastern ones noticeably predominate. Their total repeatability is 50-70%. Only in the eastern part of the sea, south of 50°N, south and southwest winds are quite often observed, and in some places also southeast. The wind speed in the coastal zone is on average 6-8 m/s, and in open areas it varies from 6 to 12 m/s, and increases from north to south. The winds of the northern, western and eastern directions carry with them cold sea Arctic air from the Arctic Ocean, and cold and dry continental polar and continental Arctic air from the Asian and American continents. With southerly winds, sea polar, and sometimes sea tropical air comes here. Above the sea, mainly the masses of continental arctic and maritime polar air interact, on the border of which the arctic front is formed. It is located somewhat north of the Aleutian arc and generally extends from the southwest to the northeast. On the frontal section of these air masses, cyclones form, moving approximately along the front to the northeast. The movement of these cyclones enhances northern winds in the west and weakening them or even changing to the southern seas in the east. Large pressure gradients caused by the Yakutian spur of the Siberian anticyclone and the Aleutian low cause very strong winds in the western part of the sea. During storms, the wind speed often reaches 30-40 m/s. Usually storms last about a day, but sometimes they last 7-9 days with some weakening. The number of days with storms in the cold season is 5-10, in some places it reaches 15-20 per month.

Water temperature on the surface of the Bering and Okhotsk seas in summer

The air temperature in winter decreases from south to north. Average monthly temperature the coldest months - January and February - is 1-4 ° in the southwestern and southern parts of the sea and -15-20 ° in the northern and north- eastern regions. In the open sea, the air temperature is higher than in the coastal zone. Off the coast of Alaska, it can drop to -40-48°. On open spaces temperatures below –24° are not observed.

In the warm season, the pressure systems are restructured. Starting from spring, the intensity of the Aleutian minimum decreases, and in summer it is very weakly expressed, the Yakut spur of the Siberian anticyclone disappears, the Polar maximum shifts to the north, and the Hawaiian maximum occupies its extreme northern position. As a result of such a synoptic situation in warm seasons, southwestern, southern and southeastern winds prevail, the frequency of which is 30-60%. Their speed in the western part of the open sea is 4-6 m/s, and in the eastern regions - 4-7 m/s. In the coastal zone, the wind speed is less. The decrease in wind speeds compared to winter values is explained by the decrease in atmospheric pressure gradients over the sea. In summer, the Arctic front shifts south of the Aleutian Islands. Cyclones are born here, with the passage of which a significant increase in winds is associated. In summer, the frequency of storms and wind speeds is less than in winter. Only in the southern part of the sea, where tropical cyclones (typhoons) penetrate, do they cause severe storms with hurricane-force winds. Typhoons in the Bering Sea are most likely from June to October, usually occur no more than once a month and last for several days. The air temperature in summer generally decreases from south to north, and it is somewhat higher in the eastern part of the sea than in the western part. The average monthly air temperatures of the warmest months - July and August - within the sea vary from about 4 ° in the north to 13 ° in the south, and they are higher near the coast than in the open sea. Relatively mild winters in the south and cold in the north, and cool, overcast summers everywhere are the main seasonal features of the weather in the Bering Sea. The continental runoff into the sea is approximately 400 km 3 per year. Most of the river water enters its northernmost part, where the largest rivers flow: Yukon (176 km 3), Kuskokwim (50 km 3 / year) and Anadyr (41 km 3 / year). About 85% of the total annual runoff occurs during the summer months. The influence of river waters on sea waters is felt mainly in the coastal zone on the northern margin of the sea in summer.

Hydrology and water circulation

Geographical position, vast expanses, relatively good connection with the Pacific Ocean through the straits of the Aleutian ridge in the south and extremely limited communication with the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait in the north determine the hydrological conditions of the Bering Sea. The components of its thermal budget depend mainly on climatic conditions and, to a much lesser extent, on heat advection by currents. In this regard, various climatic conditions in the northern and southern parts of the sea entail differences in the heat balance of each of them, which accordingly affects the water temperature in the sea.

For the water balance of the Bering Sea, on the contrary, water exchange is of decisive importance. Through the Aleutian Straits come very large quantities surface and deep ocean waters, and through the Bering Strait, waters flow into the Chukchi Sea. Precipitation (approximately 0.1% of the volume of the sea) and river runoff (approximately 0.02%) are very small in relation to the vast area and volume of sea water, therefore they are less significant in the water balance than water exchange through the Aleutian straits.

However, water exchange through these straits has not yet been sufficiently studied. It is known that large masses of surface water exit the sea into the ocean through the Kamchatka Strait. The vast majority of deep ocean water enters the sea in three regions: through the eastern half of the Middle Strait, through almost all the straits of the Fox Islands, and through the Amchitka, Tanaga and other straits between the Rat and Andrianov Islands. Perhaps more deep waters penetrate into the sea and through the Kamchatka Strait, if not constantly, then periodically or sporadically. Water exchange between the sea and the ocean affects the distribution of temperature, salinity, structure formation and general circulation of the waters of the Bering Sea.

The bulk of the waters of the Bering Sea is characterized by a subarctic structure, the main feature of which is the existence of a cold intermediate layer in summer, as well as a warm intermediate layer located below it. Only in the southernmost part of the sea, in the areas immediately adjacent to the Aleutian ridge, waters of a different structure were found, where both intermediate layers are absent.

Water temperature and salinity

Salinity on the surface of the Bering and Okhotsk seas in summer

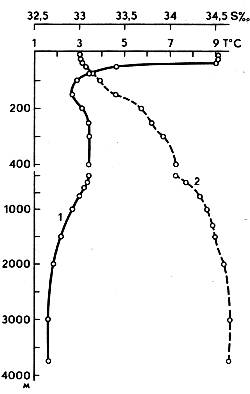

The bulk of the waters of the sea, which occupies its deep-sea part, is clearly divided into four layers in summer: surface, cold intermediate, warm intermediate and deep. Such stratification is determined mainly by differences in temperature, and the change in salinity with depth is small.

The surface water mass in summer is the most heated upper layer from the surface to a depth of 25-50 m, characterized by a temperature of 7-10° on the surface and 4-6° at the lower boundary and a salinity of about 33‰. The greatest thickness of this water mass is observed in the open part of the sea. The lower boundary of the surface water mass is the temperature jump layer. The cold intermediate layer is formed here as a result of winter convective mixing and subsequent summer heating of the upper water layer. This layer has an insignificant thickness in the southeastern part of the sea, but as it approaches the western shores, it reaches 200 m or more. The minimum temperature was recorded at horizons of about 150-170 m. In the eastern part, the minimum temperature is 2.5-3.5°, and in the western part of the sea it drops to 2° in the area of the Koryak coast and to 1° and lower in the area of the Karaginsky Bay. The salinity of the cold intermediate layer is 33.2-33.5‰ At the lower boundary of this layer, the salinity rapidly rises to 34‰.

Vertical distribution of water temperature (1) and salinity (2) in the Bering Sea

In warm years in the south, in the deep part of the sea, a cold intermediate layer may be absent in summer, then the temperature decreases relatively smoothly with depth, with a general warming of the entire water column. The origin of the intermediate layer is associated with the influx of Pacific water, which is cooled from above as a result of winter convection. Convection here reaches horizons of 150-250 m, and under its lower boundary there is an increased temperature - a warm intermediate layer. The maximum temperature varies from 3.4-3.5 to 3.7-3.9°. The depth of the core of the warm intermediate layer in the central regions of the sea is about 300 m, to the south it decreases to 200 m, and to the north and west it increases to 400 m or more. The lower boundary of the warm intermediate layer is eroded, approximately it is outlined in the 650-900 m layer.

The deep water mass, which occupies most of the volume of the sea, does not differ significantly both in depth and in the area of the sea. For more than 3000 m, the temperature varies from about 2.7-3.0 to 1.5-1.8 ° at the bottom. Salinity is 34.3-34.8‰.

As you move south to the straits of the Aleutian ridge, the stratification of waters is gradually erased, the temperature of the core of the cold intermediate layer rises, approaching in value the temperature of the warm intermediate layer. The waters are gradually acquiring a qualitatively different structure of the Pacific water.

In some areas, especially in shallow water, the main water masses change, new masses appear that have local meaning. For example, in the western part of the Gulf of Anadyr, a freshened water mass is formed under the influence of continental runoff, and in the northern and eastern parts - a cold water mass of the Arctic type. There is no warm intermediate layer here. In some shallow areas of the sea, cold waters are observed in the bottom layer in summer. Their formation is associated with the eddy circulation of water. The temperature in these cold "spots" drops to -0.5-1°.

Due to autumn-winter cooling, summer warming and mixing in the Bering Sea, the surface water mass, as well as the cold intermediate layer, are most strongly transformed. Intermediate Pacific water changes its characteristics during the year very little and only in a thin upper layer. Deep waters do not change noticeably during the year.

The temperature of the water on the sea surface generally decreases from south to north, and in the western part of the sea the water is somewhat colder than in the eastern part. In winter, in the south of the western part of the sea, the surface water temperature is usually 1-3°, and in the eastern part - 2-3°. In the north, throughout the sea, the water temperature is kept in the range from 0 ° to -1.5 °. In spring, the water begins to warm up, and the ice begins to melt, while the temperature rises slightly. In summer, the water temperature on the surface is 9-11° in the south of the western part and 8-10° in the south of the eastern part. In the northern regions of the sea, it is 4° in the west and 4-6° in the east. In shallow coastal areas, the surface water temperature is somewhat higher than in the open areas of the Bering Sea.

The vertical distribution of water temperature in the open part of the sea is characterized by seasonal changes up to 150-200 m horizons, below which they are practically absent.

Water exchange scheme in the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea

In winter, the surface temperature, equal to about 2°, extends to horizons of 140-150 m, below it rises to about 3.5° at horizons of 200-250 m, then its value almost does not change with depth.

In spring, the water temperature on the surface rises to about 3.8 ° and remains up to horizons of 40-50 m, then to horizons of 65-80 m it sharply, and then (up to 150 m) very smoothly decreases with depth and slightly increases from a depth of 200 m to the bottom.

In summer, the water temperature on the surface reaches 7-8°, but very sharply (up to 2.5°) drops with a depth of up to 50 m, below its vertical course is almost the same as in spring.

In the general water temperature in the open part of the Bering Sea, the relative uniformity of the spatial distribution in the surface and deep layers and relatively small seasonal fluctuations are characteristic, which manifest themselves only up to horizons of 200-300 m.

The salinity of the surface waters of the sea varies from 33-33.5‰ in the south to 31‰ in the east and northeast and up to 28.6‰ in the Bering Strait. Water is most significantly desalinated in spring and summer in the confluence areas of the Anadyr, Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers. However, the direction of the main currents along the coast limits the influence of the continental runoff on the deep sea areas.

The vertical distribution of salinity is almost the same in all seasons of the year. From the surface to the horizon of 100-125 m, it is approximately equal to 33.2-33.3‰. Salinity slightly increases from horizons 125-150 to 200-250 m, deeper remains almost unchanged to the bottom.

In accordance with small spatiotemporal changes in temperature and salinity, the density also changes insignificantly. The depth distribution of oceanological characteristics indicates a relatively weak vertical stratification of the waters of the Bering Sea. In combination with strong winds, this creates favorable conditions for the development of wind mixing. In the cold season, it covers the upper layers up to horizons of 100-125 m, in the warm season, when the waters are more sharply stratified and the winds are weaker than in autumn and winter, wind mixing penetrates to horizons of 75-100 m in deep and up to 50-60 m in coastal areas.

Significant cooling of the waters, and in the northern regions and intense ice formation, contribute to the good development of autumn-winter convection in the sea. During October - November, it captures the surface layer of 35-50 m and continues to penetrate deeper.

The boundary of penetration of winter convection deepens when approaching the coast due to enhanced cooling near the continental slope and shallows. In the southwestern part of the sea, this depression is especially large. The observed sinking of cold waters along the coastal slope is associated with this.

Due to the low air temperature due to the high latitude northwestern region, winter convection develops here very intensively and, probably, already in mid-January (due to the shallowness of the area) reaches the bottom.

currents

As a result of the complex interaction of winds, the inflow of water through the straits of the Aleutian ridge, tides and other factors, a field of constant currents in the sea is created.

The predominant mass of water from the ocean enters the Bering Sea through eastern part the Middle Strait, as well as through other significant straits of the Aleutian ridge.

The waters entering through the Near Strait and spreading first into eastbound, then turn north. At a latitude of about 55°, these waters merge with the waters coming from the Amchitka Strait, forming the main flow of the central part of the sea. This current maintains the existence of two stable circulations here - a large, cyclonic one, covering the central deep part of the sea, and a less significant, anticyclonic one. The waters of the main stream are directed to the northwest and reach almost to the Asian shores. Here, most of the water turns along the coast to the southwest, giving rise to the cold Kamchatka Current, and exits into the ocean through the Kamchatka Strait. Some of this water is discharged into the ocean through western part the Middle Strait, and a very small part is included in the main circulation.

The waters entering through the eastern straits of the Aleutian ridge also cross the central basin and move to the north-north-west. Approximately at a latitude of 60 °, these waters are divided into two branches: a northwestern one, heading towards the Gulf of Anadyr and further northeast, into the Bering Strait, and a northeastern one, moving towards Norton Sound Bay, and then northward, into the Bering Strait. strait.

The velocities of constant currents in the sea are small. Highest values(up to 25-50 cm/s) are observed in the areas of the straits, and in the open sea they are equal to 6 cm/s, and the velocities are especially low in the zone of the central cyclonic circulation.

Tides in the Bering Sea are mainly due to the propagation of a tidal wave from the Pacific Ocean.

In the Aleutian Straits, the tides have an irregular diurnal and irregular semidiurnal character. Near the coast of Kamchatka, during the intermediate phases of the Moon, the tide changes from semidiurnal to diurnal, at high declinations of the Moon it becomes almost purely diurnal, and at low declinations it becomes semidiurnal. At the Koryak coast, from the Olyutorsky Bay to the mouth of the river. Anadyr, the tide is irregular semi-diurnal, and near the coast of Chukotka - the correct semi-diurnal. In the area of Provideniya Bay, the tide again changes into an irregular semi-diurnal one. In the eastern part of the sea, from Cape Prince of Wales to Cape Nome, tides have both regular and irregular semidiurnal character.

South of the mouth of the Yukon, the tide becomes irregularly semidiurnal.

Tidal currents in the open sea are circular in nature, and their speed is 15-60 cm/s. Near coasts and in straits tidal currents reversible, and their speed reaches 1-2 m/s.

The cyclonic activity that develops over the Bering Sea causes the occurrence of very strong and sometimes prolonged storms. Especially strong excitement develops from November to May. At this time of the year, the northern part of the sea is covered with ice, and therefore the strongest waves are observed in the southern part. Here, in May, the frequency of waves over 5 points reaches 20-30%, and in the northern part of the sea, due to ice, it is absent. In August, waves and swell over 5 points reach their greatest development in the eastern part of the sea, where the frequency of such waves reaches 20%. IN autumn time in the southeastern part of the sea, the frequency of strong waves is up to 40%.

With prolonged winds of medium strength and significant acceleration of waves, their height reaches 6-8 m, with a wind of 20-30 m / s or more - up to 10 m, and in some cases - up to 12 or even 14 m. Periods of storm waves reach up to 9-11 s, and with moderate excitement - up to 5-7 s.

Kunashir Island

In addition to wind waves, swell is observed in the Bering Sea, the highest frequency of which (40%) occurs in autumn. In the coastal zone, the nature and parameters of the waves are very different depending on the physical and geographical conditions of the area.

ice coverage

Most of the year, a significant part of the Bering Sea is covered with ice. Ice in the sea is of local origin, i.e. formed, destroyed and melted in the sea itself. Winds and currents bring an insignificant amount of ice from the Arctic Basin into the northern part of the sea through the Bering Strait, which usually does not penetrate south of about. St. Lawrence.

The northern and southern parts of the sea differ in terms of ice conditions. The approximate boundary between them is the extreme southern position of the ice during the year - in April. This month, the edge goes from Bristol Bay through the Pribylov Islands and further west along the 57-58th parallel, and then drops south to the Commander Islands and runs along the coast to the southern tip of Kamchatka. The southern part of the sea does not freeze at all. Warm Pacific waters entering the Bering Sea through the Aleutian Straits push the floating ice to the north, and the ice edge in the central part of the sea is always curved to the north.

The process of ice formation begins first in the northwestern part of the Bering Sea, where ice appears in October and gradually moves south. Ice appears in the Bering Strait in September. In winter, the strait is filled with solid broken ice drifting to the north.

In the Gulf of Anadyr and Norton Sound, ice can be found as early as September. In early November, ice appears in the area of Cape Navarin, and in mid-November it spreads to Cape Olyutorsky. Off the coast of Kamchatka and the Commander Islands, floating ice usually appears in December, and only as an exception in November. During winter, the entire northern part of the sea, approximately up to the 60 ° parallel, is filled with heavy, hummocky ice, the thickness of which reaches 6-10 m. South of the parallel of the Pribylov Islands, there are broken ice and separate ice fields.

However, even at the time of the greatest development of ice formation, the open part of the Bering Sea is never covered with ice. In the open sea, under the influence of winds and currents, ice is in constant motion, and strong compression often occurs. This leads to the formation of hummocks, maximum height which can reach up to 20 m. Due to periodic compression and rarefaction of ice associated with tides, ice heaps, numerous polynyas and leads are formed.

The immovable ice that forms in winter in closed bays and gulfs can be broken and carried out to sea during storm winds. The ice of the eastern part of the sea is carried to the north, into the Chukchi Sea.

In April, the floating ice boundary moves to the south as far as possible. Since May, the ice begins to gradually break down and retreat to the north. During July and August, the sea is completely ice-free, but even during these months, ice can be found in the Bering Strait. Strong winds contribute to the destruction of the ice cover and the cleansing of the sea from ice in summer.

In bays and gulfs, where the freshening effect of river runoff is felt, the conditions for ice formation are more favorable than in the open sea. Big influence winds affect the location of the ice. Surge winds often clog individual bays, bays and straits. heavy ice brought from the open sea. Offshore winds, on the contrary, carry the ice into the sea, sometimes clearing the entire coastal area.

bird market

Economic importance

The fish of the Bering Sea are represented by more than 400 species, of which only no more than 35 are important commercial ones. These are salmon, cod, flounder. Perch, grenadier, capelin, coalfish, etc. are also caught in the sea.

Posted Sun, 09/11/2014 - 07:55 by Cap

The Bering Sea is the northernmost of our Far Eastern seas. It is, as it were, wedged between two huge continents of Asia and America and separated from the Pacific Ocean by the islands of the Commander-Aleutian arc.

It has predominantly natural boundaries, but in some places its limits are delineated by conditional lines. northern border of the sea coincides with the southern one and runs along the line of Cape Novosilsky () - Cape York (Seward Peninsula), the eastern one - along the coast of the American mainland, the southern one - from Cape Khabuch (Alaska) through the Aleutian Islands to Cape Kamchatsky, while the western one - along the coast of the Asian continent. Within these boundaries, the Bering Sea occupies the space between the parallels 66°30 and 51°22′ N. sh. and meridians 162°20′ E. and 157° W. e. Its general pattern is characterized by a narrowing of the contour from south to north.

The Bering Sea is the largest and deepest among the seas of the USSR and one of the largest and deepest on Earth.

Its area is 2315 thousand km2, the volume is 3796 thousand km3, the average depth is 1640 m, the largest is 4151 m. mixed continental-oceanic type.

There are few islands in the vast expanses of the Bering Sea. Apart from its boundary Aleutian island arc and the Commander Islands, in the sea itself there are large Karaginsky Islands in the west and several large islands (St. Lawrence, St. Matthew, Nelson, Nunivak, St. Paul, St. George) in the east.

The sea is named after the navigator Vitus Bering, under whose leadership it was explored in 1725-1743.

On Russian maps of the 18th century, the sea is called the Kamchatka, or the Beaver Sea. For the first time, the name Bering Sea was proposed by the French geographer Sh. P. Fliorier at the beginning of the 19th century, but it was introduced into wide use only in 1818 by the Russian navigator V. M. Golovnin.

On June 1, 1990, in Washington, Eduard Shevardnadze, then Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR, together with US Secretary of State James Baker, signed an agreement on the transfer of the Bering Sea to the United States along the Shevardnadze-Baker dividing line.

Physical location

Area 2.315 million sq. km. The average depth is 1600 meters, the maximum depth is 4151 meters. The length of the sea from north to south is 1,600 km, from east to west - 2,400 km. The volume of water is 3,795 thousand cubic meters. km.

The Bering Sea is marginal. It is located in the North Pacific Ocean and separates the Asian and North American continents. In the northwest, it is limited by the coasts of Northern Kamchatka, the Koryak Highlands, and Chukotka; in the northeast - the coast of Western Alaska.

The southern boundary of the sea is drawn along the chain of the Commander and Aleutian Islands, which form a giant arc curved to the south and separate it from the open waters of the Pacific Ocean. in the north it connects with the Arctic Ocean and numerous straits in the chain of the Commander-Aleutian ridge in the south with the Pacific Ocean.

The sea coast is indented with bays and capes. Large bays on the Russian coast: Anadyr, Karaginsky, Olyutorsky, Korfa, Cross; on the American coast: Norton, Bristol, Kuskokwim.

The islands are mainly located on the border of the sea:

US Territory (Alaska):

Pribilof Islands, Aleutian Islands, Diomede Islands (eastern - Krusenstern Island), St. Lawrence Island, Nunivak, King Island, St. Matthew Island.

territory of Russia.

Kamchatka Territory: Commander Islands, Karaginsky Island.

The large Yukon and Anadyr rivers flow into the sea.

The air temperature over the water area is up to +7, +10 °C in summer and -1, -23 °C in winter. Salinity 33-34.7‰.

Every year from the end of September, ice forms, which melts in July. The surface of the sea (except for the Bering Strait) is annually covered with ice for about ten months (about five months half of the sea, about seven months, from November to May, - the northern third of the sea). The Gulf of Laurentia in some years is not cleared of ice at all. In the western part of the Bering Strait, ice brought by the current can occur even in August.

whale hunting in the Bering Sea

Bottom relief

The relief of the sea bottom differs greatly in the northeastern part, shallow (see Beringia), located on the shelf with a length of more than 700 km, and the southwestern, deep-water, with depths of up to 4 km. Conventionally, these zones are separated along the isobath of 200 meters. The transition from the shelf to the ocean bed passes along a steep continental slope. The maximum depth of the sea (4151 meters) was recorded at the point with coordinates - 54 ° N. sh. 171°W (G) (O) in the south of the sea.

The bottom of the sea is covered with terrigenous sediments - sand, gravel, shell rock in the shelf zone and gray or green diatom silt in deep water places.

temperature and salinity

The surface water mass (up to a depth of 25-50 meters) throughout the sea in summer has a temperature of 7-10 °C; in winter temperatures drop to -1.7-3 °C. The salinity of this layer is 22-32 ppm.

The intermediate water mass (layer from 50 to 150–200 m) is colder: the temperature, which varies little over the seasons, is approximately −1.7 °C, salinity is 33.7–34.0‰.

Below, at depths up to 1000 m, there is a warmer water mass with temperatures of 2.5-4.0 ° C, salinity of 33.7-34.3 ‰.

The deep water mass occupies all the near-bottom areas of the sea with depths of more than 1000 m and has temperatures of 1.5-3.0 ° C, salinity - 34.3-34.8 ‰.

Ichthyofauna

The Bering Sea is inhabited by 402 species of fish of 65 families, including 9 species of gobies, 7 species of salmon, 5 species of eelpouts, 4 species of flatfish and others. Of these, 50 species and 14 families are commercial fish. Fishing objects are also 4 species of crabs, 4 species of shrimp, 2 species of cephalopods.

Main marine mammals The Bering Sea are animals from the order of pinnipeds: ringed seal (akiba), common seal (larga), bearded seal (beared seal), lionfish and Pacific walrus. From cetaceans - narwhal, gray whale, bowhead whale, humpback whale, fin whale, Japanese (southern) whale, sei whale, northern blue whale. Walruses and seals form rookeries along the coast of Chukotka.

Ports:

Provideniya, Anadyr (Russia), Nome (USA).

There is no permanent population on the island, but the base of Russian border guards is located here.

The highest point is Mount Roof, 505 meters.

It is located a little south of the geographical center of the island.

KRUZENSHTERNA ISLAND

Krusenstern Island (eng. Little Diomede, translated as "Little Diomede", the Eskimo name Ingalik, or Ignaluk (Inuit. Ignaluk) - "opposite") is the eastern island (7.3 km²) of the Diomede Islands. It belongs to the USA. State - Alaska.

village on Krusenstern Island, USA, Alaska

Located 3.76 km from the island, it belongs to Russia. In the center of the strait between the islands is the state maritime border between Russia and the United States. From Ratmanov Island to 35.68 km. Bering Sea

The most low point(316 m below sea level) - the bottom of the Kuril lake.

Climate

The climate is generally humid and cool. Abnormally colder and windier on the lowland coasts (especially on the western coast) than in the center, in the Kamchatka River valley, fenced off mountain ranges from the prevailing winds.

Winter - the first snow usually falls in early November, and the last melts only in August. Mountain peaks are covered with new snow already in August-September. Throughout the coastal area, winters are warm, mild, and snowy; in the continental part and in the mountains, they are cold and frosty with long, dark nights and very short days.

The calendar spring (March-April) is the best time for skiing: the snow is dense, the weather is sunny, the day is long.

The actual spring (May, June) is short and fast. Vegetation rapidly captures the territories freed from snow and covers all free space.

Summer, in the generally accepted concept, in Kamchatka happens only in the continental part of the peninsula. From June to August, mostly cold wet cloudy weather with rain, fog and low dense overcast.

Autumn (September, October) is usually cloudy, dry and warm. Sometimes warmer than summer.

Major islands:

Bering

Copper

Small islands and rocks:

around Bering Island:

Toporkov

Arius Stone

Aleut stone

Stone Nadvodny (Emelyanovsky)

Stone Half (Half)

Sivuchy Stone

around Medny Island:

beaver stones

Waxmouth Stone

Kekur Ship Post

Sivuchy Stone

Sivuchy Stone East

as well as a number of nameless rocks.

(Chuk. Chukotkaken Autonomous Okrug) is a subject of the Russian Federation in the Far East.

It borders on the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), the Magadan Region and the Kamchatka Territory. In the east it has a maritime border with the United States.

The entire territory of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug belongs to the regions of the Far North.

The administrative center is the city of Anadyr.

It was formed by the decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of December 10, 1930 "On the organization of national associations in the areas of settlement of small nationalities of the North" as part of the Far Eastern Territory. included the following areas: Anadyr (center Novo-Mariinsk, aka Anadyr), Eastern tundra (center Ostrovnoye), Western tundra (center Nizhne-Kolymsk), Markovsky (center Markovo), Chaunsky (center in the Chaun Bay) and Chukotsky (center in the Chukotka cultural base - Bay of St. Lawrence), transferred a) from the Far East Territory Anadyr and Chukotka regions completely; b) from the Yakut ASSR, the territory of the Eastern tundra with a border along the right bank of the Alazeya River and the Western tundra, regions of the middle and downstream Omolon river.

During the zoning of the region in October-November 1932, it was left "within its former borders as an independent national district directly subordinate to the region."

On July 22, 1934, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee decided to include the Chukotka and Koryaksky national districts in the Kamchatka region. However, such subordination was of a rather formal nature, since from 1939-1940 the territory of the district was under the jurisdiction of Dalstroy, which carried out full administrative and economic management in the territories subordinate to it.

On May 28, 1951, by the decision of the Presidium of the USSR Armed Forces, the district was allocated to the direct subordination of the Khabarovsk Territory.

From December 3, 1953 he was part of Magadan region.

In 1980, after the adoption of the law of the RSFSR "On Autonomous Okrugs of the RSFSR" in accordance with the Constitution of the USSR of 1977, the Chukotka National Okrug became autonomous.

July 16, 1992 Chukotsky autonomous region withdrew from the Magadan region and received the status of a subject of the Russian Federation.

Currently, it is the only autonomous okrug out of four that is not part of another subject of the Russian Federation.

settlement Egvekinot Bering Sea

Border regime

The Chukotka Autonomous Okrug is a territory with a border regime.

Entry of citizens of the Russian Federation and for foreign citizens to a part of the territory of the district adjacent to the sea coast and to the islands is regulated, that is, permission from the border service of the Russian Federation or documents allowing being in the border zone is required.

Specific sections of the border zone on the territory of the district are determined by Order of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation dated April 14, 2006 N 155 "On the limits of the border zone on the territory of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug." In addition, the entire territory of the district is regulated by the entry of foreign citizens in accordance with Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of July 4, 1992 N 470 "On approval of the List of territories of the Russian Federation with regulated visits for foreign citizens", that is, in order to visit the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, it is necessary FSB permission.

WHERE IS

Chukotka Autonomous Okrug is located in the extreme northeast of Russia. It occupies the entire Chukotka Peninsula, part of the mainland and a number of islands (Wrangel, Ayon, Ratmanov, etc.).

It is washed by the East Siberian and Chukchi Seas of the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean.

The extreme points of Russia are located on the territory of the district: the eastern point is, the eastern continental point is Cape Dezhnev. Here are located: the northernmost city of Russia - Pevek and the easternmost - Anadyr, as well as the easternmost permanent settlement - Uelen.

BERINGIA - THE LEGENDARY PALEOSTRATE

Beringia is a biogeographic region and a paleogeographic country that links together northeast Asia and northwestern North America (the Bering sector of the Holarctic). Currently, it is spreading to the territories surrounding the Bering Strait, the Chukchi and Bering Seas. Includes parts of Chukotka and Kamchatka in Russia, and Alaska in the United States. In a historical context, it also included the land Bering or the Bering Isthmus, which repeatedly connected Eurasia and North America into a single supercontinent.

The study of ancient deposits on the bottom of the sea and on both sides of the Bering Strait showed that over the past 3 million years, the territory of Beringia has risen and again submerged under water at least six times. Every time the two continents joined, there was a migration of animals from the Old World to the New and back.

Bering Strait

Strictly speaking, this piece of land was not an isthmus in the traditional sense of the term, since it was a vast area of the continental shelf with a width of up to 2000 km from north to south, protruding above the sea surface or hiding under it due to cyclic changes in the level of the World Ocean. The term Beringia for the isthmus was proposed in 1937 by the Swedish botanist and geographer Eric Hulten.

The last time the continents separated was 10-11 thousand years ago, but the isthmus had existed for 15-18 thousand years before that.

Modern research shows that during this period the route from Asia to America did not remain open all the time. Two thousand years after the appearance of the last Beringia in Alaska, two giant glaciers closed, erecting an insurmountable barrier.

It is assumed that those primitive people who managed to move from Asia to America became the ancestors of some of the current peoples living on the American continent, in particular the Tlingit and Fuegians.

Shortly before the collapse of Beringia, global climate change made it possible for the ancestors of the current Indians to penetrate the isthmus.

Then, on the site of the isthmus, the modern Bering Strait formed, and the inhabitants of America were isolated for a long time. Nevertheless, the settlement of America took place later, but by sea or on ice (Eskimos, Aleuts).

Cape Navarin, Bering Sea

DETAILED GEOGRAPHY OF THE BERING SEA

Basic physical and geographical features.

The coastline of the Bering Sea is complex and highly indented. It forms many bays, bays, coves, peninsulas, capes and straits. For the nature of this sea, the straits connecting it with the Pacific Ocean are especially important. The total area of their cross section is approximately 730 km2, and the depths in some of them reach 1000–2000 m, and in Kamchatsky - 4000–4500 m, which determines the water exchange through them not only in the surface, but also in the deep horizons and determines the significant influence Pacific Ocean to this sea. The cross-sectional area of the Bering Strait is 3.4 km2, and the depth is only 42 m, so the waters of the Chukchi Sea practically do not affect the Bering Sea.

The coast of the Bering Sea, which is unequal in external forms and structure, in different areas belongs to different geomorphological types of coasts. From fig. 34 shows that they mainly belong to the type of abrasion shores, but there are also accumulative ones. The sea is mostly surrounded by high and steep shores, only in the middle part of the western and eastern coasts do wide strips of flat, low-lying tundra approach the sea. Narrower strips of the low coast are located near the mouths of small rivers in the form of a deltaic alluvial plain or border the tops of bays and bays.

The main morphological zones are clearly distinguished in the relief of the bottom of the Bering Sea: the shelf and insular shoals, the continental slope and the deep-water basin. The relief of each of them has its own characteristic features. The shelf zone with depths up to 200 m is mainly located in the northern and eastern parts of the sea, occupying more than 40% of its area. Here it adjoins the geologically ancient regions of Chukotka and Alaska. The bottom in this area of the sea is a vast, very gently sloping underwater plain about 600-1000 km wide, within which there are several islands, troughs, and small bottom elevations. The continental shelf off the coast of Kamchatka and the islands of the Commander-Aleutian ridge looks different. Here it is narrow and its relief is very complex. It borders the shores of geologically young and very mobile areas of land, within which intense and frequent manifestations of volcanism and seismicity are common. The continental slope stretches from the northwest to the southeast approximately along the line from Cape Navarin to about. Unimac. Together with the island slope zone, it occupies approximately 13% of the sea area, has depths from 200 to 3000 m and is characterized by a large distance from the coast and a complex bottom topography. The angles of inclination are large and often vary from 1–3 to several tens of degrees. The zone of the continental slope is dissected by underwater valleys, many of which are typical submarine canyons, deeply cut into the seabed and having steep and even steep slopes. Some canyons, especially near the Pribylov Islands, are distinguished by their complex structure.

The deep water zone (3000–4000 m) is located in the southwestern and central parts of the sea and is bordered by a relatively narrow strip of coastal shallows. Its area exceeds 40% of the sea area: The bottom relief is very calm. It is characterized by the almost complete absence of isolated depressions. Several existing depressions differ very little from the depth of the bed, their slopes are very gentle, i.e., the isolation of these bottom depressions is weakly expressed. There are no ridges at the bottom of the bed that block the sea from coast to coast. Although the Shirshov Ridge approaches this type, it has a relatively shallow depth on the ridge (mainly 500–600 m with a saddle of 2500 m) and does not come close to the base of the island arc: it is limited in front of the narrow but deep (about 3500 m) Ratmanov Trench. The greatest depths of the Bering Sea (more than 4000 m) are located in the Kamchatka Strait and near the Aleutian Islands, but they occupy a small area. Thus, the bottom relief determines the possibility of water exchange between the individual parts of the sea: without any restrictions within the depths of 2000-2500 m, with some limitation determined by the section of the Ratmanov trough, up to depths of 3500 m, and with an even greater restriction at greater depths. However, the weak isolation of the basins does not allow the formation of waters in them that differ significantly in their properties from the main mass.

The geographical position and large spaces determine the main features of the climate of the Bering Sea. It is almost entirely located in the subarctic climatic zone, and only its extreme northern part (to the north of 64 ° N) belongs to the Arctic zone, and the southernmost part (to the south of 55 ° N) belongs to the zone of temperate latitudes. In accordance with this, there are certain climatic differences between different areas of the sea. North of 55-56° N. sh. in the climate of the sea, especially its coastal regions, the features of continentality are noticeably expressed, but in the spaces remote from the coast they are much weaker. South of these (55-56°N) parallels, the climate is mild, typically maritime. It is characterized by small daily and annual air temperature amplitudes, high cloud cover and a significant amount of precipitation. As you get closer to the coast, the influence of the ocean on the climate decreases. Due to stronger cooling and less significant heating of the part of the Asian continent adjacent to the sea than the American one, the western regions of the sea are colder than the eastern ones. Throughout the year, the Bering Sea is under the influence of permanent centers of atmospheric action - the Polar and Honolulu maxima, the position and intensity of which are not constant from season to season and the degree of their influence on the sea changes accordingly. In addition, it is also affected by seasonal large-scale baric formations: the Aleutian Low, the Siberian High, the Asian and Lower American depressions. Their complex interaction determines certain seasonal features of atmospheric processes.

In the cold season, especially in winter, the sea is mainly influenced by the Aleutian Low, as well as the Polar High and the Yakutsk spur of the Siberian Anticyclone. Sometimes the influence of the Honolulu High is felt, which at this time of the year occupies the extreme southeast position. This synoptic setting results in a wide variety of winds over the sea. At this time, winds of almost all directions are observed here with greater or lesser frequency. However, northwest, north and northeast winds prevail. Their total repeatability is 50-70%. Only in the eastern part of the sea south of 50° N. sh. quite often (30-50% of cases) south and south-west winds are observed, and in some places also south-east. Wind speed in the coastal zone averages 6-8 m/s, and in open areas it varies from 6 to 12 m/s, and increases from north to south.

The winds of the northern, western and eastern directions carry with them cold maritime Arctic air from the Arctic Ocean, and cold and dry continental polar and continental Arctic air from the Asian and American continents. With the winds of the southern directions, the cloudy polar, and at times the sea tropical air comes here. Above the sea, the masses of the continental arctic and maritime polar air interact predominantly, at the junction of which the arctic front is formed. It is located somewhat north of the Aleutian arc and generally extends from the southwest to the northeast. On the frontal section of these air masses, cyclones form, moving approximately from the southwest to the northeast. The movement of these cyclones contributes to the strengthening of the northern winds in the west and their weakening or even change to the southern and eastern seas.

Large pressure gradients due to the Yakutian spur of the Siberian anticyclone and the Aleutian low cause very strong winds in the western part of the sea. During storms, the wind speed often reaches 30–40 m/s. Storms usually last about a day, but sometimes they last 7–9 days with some weakening. The number of days with storms in the cold season is 5-10, in places up to 15-20 per month.

The air temperature in winter decreases from south to north. Its average monthly values for the coldest months (January and February) are +1-4° in the south-western and southern parts of the sea and -15-20° in its northern and north-eastern regions, and in the open sea the air temperature is higher than in the coastal zone, where it (off the coast of Alaska) can reach −40–48°. In open spaces, temperatures below -24 ° are not observed.

In the warm season, the pressure systems are restructured. Beginning in spring, the intensity of the Aleutian minimum decreases; in summer, it is very weakly expressed. The Yakut spur of the Siberian anticyclone disappears, the Polar High shifts to the north, and the Honolu High takes its extreme northwestern position. As a result of the current synoptic situation, southwestern, southern, and southeastern winds predominate in warm seasons, with a frequency of 30–60%. Their speed in the western part of the open sea is 4–5 m/s, and in its eastern regions, 4–7 m/s. In the coastal zone, the wind speed is less. The decrease in wind speed compared to winter values is explained by the decrease in atmospheric pressure gradients over the sea. In summer, the Arctic front is located somewhat south of the Aleutian Islands. Cyclones are born here, with the passage of which a significant increase in winds is associated. In summer, the frequency of storms and wind speeds is less than in winter. Only in the southern part of the sea, where tropical cyclones (locally called typhoons) penetrate, do they cause severe storms with hurricane-force winds. Typhoons in the Bering Sea are most likely from June to October, usually occur no more than once a month and last for several days.

The air temperature in summer generally decreases from south to north and is slightly higher in the eastern part of the sea than in the western part. The average monthly air temperatures of the warmest months (July and August) within the sea vary from about 4 to 13°, and they are higher near the coast than in the open sea. Relatively mild in the south and cold in the north winters and cool, overcast summers everywhere are the main seasonal features of the weather in the Bering Sea.

With the enormous volume of the waters of the Bering Sea, the continental flow into it is small and equals approximately 400 km3 per year. The vast majority of river water enters its northernmost part, where the largest rivers flow: Yukon (176 km3), Kuskokwim (50 km3) and Anadyr (41 km3). About 85% of the total annual runoff occurs during the summer months. The influence of river waters on sea waters is felt mainly in the coastal zone on the northern margin of the sea in summer.

Geographical position, vast expanses, relatively good communication with the Pacific Ocean through the straits of the Aleutian ridge in the south and extremely limited communication with the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait in the north are the determining factors in the formation of the hydrological conditions of the Bering Sea. The components of its thermal budget depend mainly on climatic indicators and, to a much lesser extent, on the flow of heat in and out by currents. In this regard, unequal climatic conditions in the northern and southern parts of the sea entail differences in the heat balance of each of them, which accordingly affects the water temperature in the sea.

For its water balance, water exchange through the Aleutian Straits is of decisive importance, through which very large amounts of surface and deep Pacific waters enter and waters flow out of the Bering Sea. Precipitation (about 0.1% of the volume of the sea) and river runoff (about 0.02%) are small in relation to the vast area of the sea, so they are significantly less significant in the inflow and outflow of moisture than water exchange through the Aleutian straits.

However, water exchange through these straits has not yet been sufficiently studied. It is known that large masses of surface water exit the sea into the ocean through the Kamchatka Strait. The overwhelming amount of deep ocean water enters the sea in three areas: through the eastern half of the Middle Strait, through almost all the straits of the Fox Islands, through the Amchitka, Tanaga and other straits between the Rat and Andreyanovsky Islands. It is possible that deeper waters penetrate the sea through the Kamchatka Strait, if not constantly, then periodically or sporadically. Water exchange between the sea and the ocean affects the distribution of temperature, salinity, structure formation and general circulation of the waters of the Bering Sea.

Cape Lesovsky

Hydrological characteristic.

The temperature of the water on the surface generally decreases from south to north, and in the western part of the sea the water is somewhat colder than in the east. In winter, in the south of the western part of the sea, the surface water temperature is usually 1-3°, and in the eastern part it is 2-3°. In the north, throughout the sea, the water temperature is kept in the range from 0 ° to -1.5 °. In spring, waters begin to warm up and ice melts, while the increase in water temperature is relatively small. In summer, the surface water temperature is 9–11° in the south of the western part and 8–10° in the south of the eastern part. In the northern regions of the sea, it is 4–8° in the west and 4–6° in the east. In shallow coastal areas, the surface water temperature is somewhat higher than the values given for open areas of the Bering Sea (Fig. 35).

The vertical distribution of water temperature in the open part of the sea is characterized by its seasonal changes up to 250-300 m horizons, below which they are practically absent. In winter, the surface temperature, which is approximately 2°, extends to horizons of 140-150 m, from which it rises to approximately 3.5° at horizons of 200-250 m, after which its value hardly changes with depth. Spring warming raises the surface water temperature to about 3.8°C. This value is preserved up to horizons of 40-50 m, from which it initially (up to horizons of 75-80 m) sharply, and then (up to 150 m) very smoothly decreases with depth, then (up to 200 m) the temperature noticeably (up to 3 ° ), and deeper it slightly rises to the bottom.

In summer, the water temperature on the surface reaches 7-8°, but it drops very sharply (up to +2.5°) with a depth of 50 m, from where its vertical course is almost the same as in spring. Autumn cooling lowers the surface water temperature. However, the general nature of its distribution at the beginning of the season resembles spring and summer, and by the end it changes to winter look. In the general water temperature in the open part of the Bering Sea, the relative uniformity of the spatial distribution in the surface and deep layers and relatively small amplitudes of seasonal fluctuations are characteristic, which manifest themselves only up to horizons of 200–300 m.

The salinity of the surface waters of the sea varies from 33.0–33.5‰ in the south to 31.0‰ in the east and northeast and 28.6‰ in the Bering Strait (Fig. 36). The most significant desalination occurs in spring and summer at the confluence of the Anadyr, Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers. However, the direction of the main currents along the coast limits the influence of the continental runoff on the deep sea areas. The vertical distribution of salinity is almost the same in all seasons of the year. From the surface to horizons of 100–125 m, it is approximately equal to 33.2–33.3‰. Its slight increase occurs from horizons 125-150 to 200-250 m, deeper it remains almost unchanged to the bottom.

walrus rookery on the Chukchi coast

In accordance with the small spatiotemporal changes in temperature and salinity, the variation in density is equally small. The depth distribution of oceanological characteristics indicates a relatively weak vertical stratification of the waters of the Bering Sea. In combination with strong winds, this creates favorable conditions for the development of wind mixing in it. In the cold season, it covers the upper layers up to horizons of 100-125 m; in the warm season, when the waters are more sharply stratified and the winds are weaker than in autumn and winter, wind mixing penetrates to horizons of 75-100 m in deep and up to 50-60 m in coastal areas.

Significant cooling of the waters, and in the northern regions and intense ice formation, contribute to the good development of autumn-winter convection in the sea. During October-November, it captures the surface layer of 35-50 m and continues to penetrate deeper; in this case, heat is transferred to the atmosphere by the sea. The temperature of the entire layer captured by convection at this time of the year decreases, as calculations show, by 0.08-0.10° per day. Further, due to a decrease in the temperature difference between water and air and an increase in the thickness of the convection layer, the water temperature drops somewhat more slowly. Thus, in December-January, when a completely homogeneous surface layer, cooled (in the open sea) to approximately 2.5°C, is formed in the Bering Sea and is of considerable thickness (down to a depth of 120-180 m), the temperature of the entire layer captured by convection decreases by 0 per day. .04—0.06°.

The boundary of penetration of winter convection deepens when approaching the coast, due to enhanced cooling near the continental slope and shallows. In the southwestern part of the sea, this depression is especially large. The observed sinking of cold waters along the coastal slope is associated with this. Due to the low air temperature, due to the high latitude of the northwestern region, winter convection develops very intensively here and, probably, already in mid-January, due to the shallowness of the region, it reaches the bottom.

The bulk of the waters of the Bering Sea is characterized by a subarctic structure, the main feature of which is the existence of a cold intermediate layer in summer, as well as a warm intermediate layer located below it. Only in the southernmost part of the sea, in the areas immediately adjacent to the Aleutian ridge, waters of a different structure were found, where both intermediate layers are absent.

The bulk of the waters of the sea, which occupies its deep-sea part, is clearly divided into four layers in summer: surface, cold intermediate, warm intermediate and deep. Such stratification is determined mainly by differences in temperature, and the change in salinity with depth is small.

The surface water mass in summer is the most heated upper layer from the surface to a depth of 25–50 m, characterized by a temperature of 7–10° at the surface and 4–6° at the lower boundary and a salinity of about 33.0‰. The greatest thickness of this water mass is observed in the open part of the sea. The lower boundary of the surface water mass is the temperature jump layer. The cold intermediate layer is formed as a result of winter convective mixing and subsequent summer heating of the upper water layer. This layer has an insignificant thickness in the southeastern part of the sea, but as it approaches the western shores, it reaches 200 m or more. It has a noticeable temperature minimum, located on average at horizons of about 150–170 m. and lower in the area of the Karaginsky Bay. The salinity of the cold intermediate layer is 33.2–33.5‰. At the lower boundary of the layer, salinity rapidly rises to 34‰. In warm years, in the south of the deep part of the sea, a cold intermediate layer may be absent in summer, then the vertical temperature distribution is characterized by a relatively smooth decrease in temperature with depth, with a general warming of the entire water column. The warm intermediate layer originates from the transformation of Pacific water. From the Pacific Ocean comes relatively warm water, which is cooled from above as a result of winter convection. Convection here reaches horizons of the order of 150-250 m, and under its lower boundary an elevated temperature is observed - a warm intermediate layer. The temperature maximum varies from 3.4-3.5 to 3.7-3.9°. The depth of the core of the warm intermediate layer in the central regions of the sea is approximately 300 m; to the south it decreases to about 200 m, and to the north and west it increases to 400 m or more. The lower boundary of the warm intermediate "layer is eroded, approximately it is outlined in the 650-900 m layer.

The deep water mass, which occupies most of the volume of the sea, does not show significant differences in its characteristics both in depth and from region to region. For more than 3000 m in depth, the temperature varies from about 2.7-3.0 to 1.5-1.8° at the bottom. Salinity is 34.3–34.8‰.

As we move south and approach the straits of the Aleutian ridge, the stratification of waters is gradually erased, the temperature of the core of the cold intermediate layer, increasing in value, approaches the temperature of the warm intermediate layer. The waters gradually pass into a qualitatively different structure of the Pacific water.